I first watched this film out of genuine curiosity. I stumbled across it one night on BBC iPlayer and immediately got my heart broken and my soul crushed by this beautiful film, the biopic-Esque film loosely inspired by Charlotte Wells’ own childhood. After stumbling upon this film, it found me again when I began university. This was the first film my lecturer showed my class. I vividly remember bursting into tears in the middle of the film, and just missing my parents so much and missing being young and innocent like Sophie’s character at the beginning of the film. Overall, this film is incredibly beautiful and meaningful. Wells’ decision to use a non-linear narrative showing both older and younger Sophie’s perspective’s showing how her understanding of what her father is going through shifts throughout the film.

As Wells presents the film from Sophie’s perspective, it highlights the lack of understanding of her father’s depressive state at the beginning of the film in comparison to the ending, when she is an adult looking back on her memories of their final holiday together. The use of false archive footage through the use of the camcorder Sophie consistently uses throughout their holiday. The visual aesthetic of this footage connotes a hugely nostalgic feeling to the footage, as the target audience of the film is young adults; it can be argued that the nostalgic feeling taken from the footage can be applied to the audience’s own archive footage of holidays they took when they were younger. Personally, I felt extremely nostalgic about past holidays my family had taken while watching this film. I feel the film addresses the fact that you never really know when your last ‘typical’ childhood holiday will be. Looking back on my childhood now, I can’t really pinpoint when my last one was; it just ended one day as I grew up.

The image above showcases Sophie’s young age, as Frankie Corio was twelve years old when filming Aftersun. As she was so young upon filming, it places further emphasis upon her character’s innocence, which is further amplified by the use of a Dutch angle within the shot. The use of the angle suggests an underlying sense of anxiousness. Sophie’s young age and innocence are clearly evident in her facial expression as she appears through the distorted lens of the film camera. The camera is an essential part of the entire narrative of the film, as both Sophie and Calum use it throughout the film; the repeated motif allows the audience to speculate on the importance of memory in reference to the film. It can be argued that the importance of memory is especially poignant towards the end of the film, as it’s revealed that an older Sophie has found this footage and uses it to help piece together her fragmented memories from her last holiday with her father.

Truly, one cannot talk about this film without mentioning the iconic ‘Under Pressure’ dance sequence at the end would honestly be a crime. This sequence is one of my favourites of the entire film; it can be argued that this sequence shows Sophie’s understanding of what’s happening to her father shifting in real time. As the sequence opens with Sophie being embarrassed by Calum’s dancing, a typical reaction from a young girl. But as the scene progresses, she becomes more active in the movement, creating the argument that an unspoken understanding is reached between the two characters.

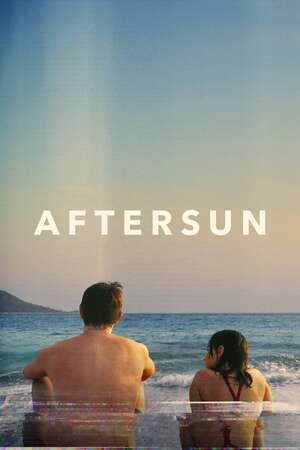

The figure above helps argue the idea of an unspoken agreement between the two characters. The use of warm lighting creates a sense of comfort and familiarity for the audience, alongside encouraging spectators to feel that same sense of comfort when considering Sophie and Calum’s characters. The proximity between the pair in this scene further argues for a deeper sense of understanding between the pair. Something I find that hits so deep about this part in the film, and that is truly brilliant, is the fact that the song, ‘Under Pressure’, is edited into the sequence in a way that allows it to appear as both diegetic and non-diegetic. Personally, I found this choice to be exceptionally moving and evocative, it’s always this part of the film where I start crying especially hard. This part of the film is especially beautiful and moving.

Finally, the significance of the Persian rug Calum buys is also a sequence that holds incredible importance and adds many layers to the story and emotional impact of the film. Ultimately, the rug shows Calum’s desire for stability and a future he is currently unable to maintain. The purchase, being extravagant while being on a cheap holiday, is ultimately an extremely impractical decision, especially as Calum doesn’t have a stable home or job situation. However, the purchase reveals Calum’s longing for a grounded, beautiful, and stable life, a home which he can be proud of. The rug becomes a symbol of the life he wants for himself, but he feels unable to have. Additionally, it highlights how Sophie sees him in comparison to who he really is. Young Sophie does not understand why buying the rug matters or why Calum does it; however, when adult Sophie recounts this in her memory, she can understand how fragile he was and how desperately he was reaching for something to hold onto.

Through the use of low-key lighting, Wells can convey the upsetting nature of the shot above, and the audience can feel a sense of pity for Calum at this part of the film, as it’s clear he is struggling. As Calum lies outside of the centre-frame, it argues that he is emotionally and physically off-balance with the outside world. Additionally, the absence of Sophie within the shot further establishes how Calum may feel unstable and at a loss; the rug shop is a safe space for him to feel this way, as it allows Calum to indulge in his desire for something beautiful, permanent, and grounding, as he currently feels inadequate and unstable in his life. Overall, the rug leaves an impression on Sophie’s life long after he’s gone, leaving a material echo of him behind for Sophie to try and understand.

Leave a comment